Recapitulation theory

| Part of a series on |

| Evolutionary biology |

|---|

|

The theory of recapitulation, also called the biogenetic law or embryological parallelism—often expressed using Ernst Haeckel's phrase "ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny"—is an historical hypothesis that the development of the embryo of an animal, from fertilization to gestation or hatching (ontogeny), goes through stages resembling or representing successive adult stages in the evolution of the animal's remote ancestors (phylogeny). It was formulated in the 1820s by Étienne Serres based on the work of Johann Friedrich Meckel, after whom it is also known as Meckel–Serres law.

Since embryos also evolve in different ways, the shortcomings of the theory had been recognized by the early 20th century, and it had been relegated to "biological mythology"[1] by the mid-20th century.[2]

Analogies to recapitulation theory have been formulated in other fields, including cognitive development[3] and music criticism.

Embryology

[edit]Meckel, Serres, Geoffroy

[edit]The idea of recapitulation was first formulated in biology from the 1790s onwards by the German natural philosophers Johann Friedrich Meckel and Carl Friedrich Kielmeyer, and by Étienne Serres[4] after which, Marcel Danesi states, it soon gained the status of a supposed biogenetic law.[5]

The embryological theory was formalised by Serres in 1824–1826, based on Meckel's work, in what became known as the "Meckel-Serres Law". This attempted to link comparative embryology with a "pattern of unification" in the organic world. It was supported by Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, and became a prominent part of his ideas. It suggested that past transformations of life could have been through environmental causes working on the embryo, rather than on the adult as in Lamarckism. These naturalistic ideas led to disagreements with Georges Cuvier. The theory was widely supported in the Edinburgh and London schools of higher anatomy around 1830, notably by Robert Edmond Grant, but was opposed by Karl Ernst von Baer's ideas of divergence, and attacked by Richard Owen in the 1830s.[6]

Haeckel

[edit]Ernst Haeckel (1834–1919) attempted to synthesize the ideas of Lamarckism and Goethe's Naturphilosophie with Charles Darwin's concepts. While often seen as rejecting Darwin's theory of branching evolution for a more linear Lamarckian view of progressive evolution, this is not accurate: Haeckel used the Lamarckian picture to describe the ontogenetic and phylogenetic history of individual species, but agreed with Darwin about the branching of all species from one, or a few, original ancestors.[8] Since early in the twentieth century, Haeckel's "biogenetic law" has been refuted on many fronts.[9]

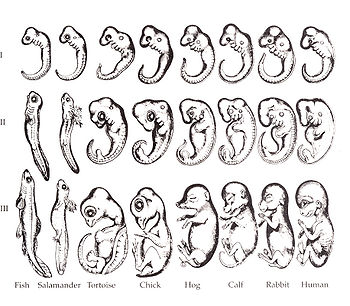

Haeckel formulated his theory as "Ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny". The notion later became simply known as the recapitulation theory. Ontogeny is the growth (size change) and development (structure change) of an individual organism; phylogeny is the evolutionary history of a species. Haeckel claimed that the development of advanced species passes through stages represented by adult organisms of more primitive species.[9] Otherwise put, each successive stage in the development of an individual represents one of the adult forms that appeared in its evolutionary history.[citation needed]

For example, Haeckel proposed that the pharyngeal grooves between the pharyngeal arches in the neck of the human embryo not only roughly resembled gill slits of fish, but directly represented an adult "fishlike" developmental stage, signifying a fishlike ancestor. Embryonic pharyngeal slits, which form in many animals when the thin branchial plates separating pharyngeal pouches and pharyngeal grooves perforate, open the pharynx to the outside. Pharyngeal arches appear in all tetrapod embryos: in mammals, the first pharyngeal arch develops into the lower jaw (Meckel's cartilage), the malleus and the stapes.

Haeckel produced several embryo drawings that often overemphasized similarities between embryos of related species. Modern biology rejects the literal and universal form of Haeckel's theory, such as its possible application to behavioural ontogeny, i.e. the psychomotor development of young animals and human children.[10]

Contemporary criticism

[edit]

Haeckel's theory and drawings were criticised by his contemporary, the anatomist Wilhelm His Sr. (1831–1904), who had developed a rival "causal-mechanical theory" of human embryonic development.[11][12] His's work specifically criticised Haeckel's methodology, arguing that the shapes of embryos were caused most immediately by mechanical pressures resulting from local differences in growth. These differences were, in turn, caused by "heredity". He compared the shapes of embryonic structures to those of rubber tubes that could be slit and bent, illustrating these comparisons with accurate drawings. Stephen Jay Gould noted in his 1977 book Ontogeny and Phylogeny that His's attack on Haeckel's recapitulation theory was far more fundamental than that of any empirical critic, as it effectively stated that Haeckel's "biogenetic law" was irrelevant.[13][14]

Darwin proposed that embryos resembled each other since they shared a common ancestor, which presumably had a similar embryo, but that development did not necessarily recapitulate phylogeny: he saw no reason to suppose that an embryo at any stage resembled an adult of any ancestor. Darwin supposed further that embryos were subject to less intense selection pressure than adults, and had therefore changed less.[15]

Modern status

[edit]Modern evolutionary developmental biology (evo-devo) follows von Baer, rather than Darwin, in pointing to active evolution of embryonic development as a significant means of changing the morphology of adult bodies. Two of the key principles of evo-devo, namely that changes in the timing (heterochrony) and positioning (heterotopy) within the body of aspects of embryonic development would change the shape of a descendant's body compared to an ancestor's, were first formulated by Haeckel in the 1870s. These elements of his thinking about development have thus survived, whereas his theory of recapitulation has not.[16]

The Haeckelian form of recapitulation theory is considered defunct.[17] Embryos do undergo a period or phylotypic stage where their morphology is strongly shaped by their phylogenetic position,[18] rather than selective pressures, but that means only that they resemble other embryos at that stage, not ancestral adults as Haeckel had claimed.[19] The modern view is summarised by the University of California Museum of Paleontology:

Embryos do reflect the course of evolution, but that course is far more intricate and quirky than Haeckel claimed. Different parts of the same embryo can even evolve in different directions. As a result, the Biogenetic Law was abandoned, and its fall freed scientists to appreciate the full range of embryonic changes that evolution can produce—an appreciation that has yielded spectacular results in recent years as scientists have discovered some of the specific genes that control development.[20]

Applications to other areas

[edit]The idea that ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny has been applied to some other areas.

Cognitive development

[edit]English philosopher Herbert Spencer was one of the most energetic proponents of evolutionary ideas to explain many phenomena. In 1861, five years before Haeckel first published on the subject, Spencer proposed a possible basis for a cultural recapitulation theory of education with the following claim:[21]

If there be an order in which the human race has mastered its various kinds of knowledge, there will arise in every child an aptitude to acquire these kinds of knowledge in the same order... Education is a repetition of civilization in little.[22]

— Herbert Spencer

G. Stanley Hall used Haeckel's theories as the basis for his theories of child development. His most influential work, "Adolescence: Its Psychology and Its Relations to Physiology, Anthropology, Sociology, Sex, Crime, Religion and Education" in 1904[23] suggested that each individual's life course recapitulated humanity's evolution from "savagery" to "civilization". Though he has influenced later childhood development theories, Hall's conception is now generally considered racist.[24] Developmental psychologist Jean Piaget favored a weaker version of the formula, according to which ontogeny parallels phylogeny because the two are subject to similar external constraints.[25]

The Austrian pioneer of psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud, also favored Haeckel's doctrine. He was trained as a biologist under the influence of recapitulation theory during its heyday, and retained a Lamarckian outlook with justification from the recapitulation theory.[26] Freud also distinguished between physical and mental recapitulation, in which the differences would become an essential argument for his theory of neuroses.[26]

In the late 20th century, studies of symbolism and learning in the field of cultural anthropology suggested that "both biological evolution and the stages in the child's cognitive development follow much the same progression of evolutionary stages as that suggested in the archaeological record".[27]

Music criticism

[edit]The musicologist Richard Taruskin in 2005 applied the phrase "ontogeny becomes phylogeny" to the process of creating and recasting music history, often to assert a perspective or argument. For example, the peculiar development of the works by modernist composer Arnold Schoenberg (here an "ontogeny") is generalized in many histories into a "phylogeny" – a historical development ("evolution") of Western music toward atonal styles of which Schoenberg is a representative. Such historiographies of the "collapse of traditional tonality" are faulted by music historians as asserting a rhetorical rather than historical point about tonality's "collapse".[28]

Taruskin also developed a variation of the motto into the pun "ontogeny recapitulates ontology" to refute the concept of "absolute music" advancing the socio-artistic theories of the musicologist Carl Dahlhaus. Ontology is the investigation of what exactly something is, and Taruskin asserts that an art object becomes that which society and succeeding generations made of it. For example, Johann Sebastian Bach's St. John Passion, composed in the 1720s, was appropriated by the Nazi regime in the 1930s for propaganda. Taruskin claims the historical development of the St John Passion (its ontogeny) as a work with an anti-Semitic message does, in fact, inform the work's identity (its ontology), even though that was an unlikely concern of the composer. Music or even an abstract visual artwork can not be truly autonomous ("absolute") because it is defined by its historical and social reception.[28]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ George Romanes's 1892 version of the figure is often attributed incorrectly to Haeckel.

References

[edit]- ^ Ehrlich, Paul R.; Holm, Richard W.; Parnell, Dennis (1963). The process of evolution. New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 66. ISBN 0-07-019130-1. OCLC 255345.

Its shortcomings have been almost universally pointed out by modern authors, but the idea still has a prominent place in biological mythology. The resemblance of early vertebrate embryos is readily explained without resort to mysterious forces compelling each individual to reclimb its phylogenetic tree.

- ^ Blechschmidt, Erich (1977). The beginnings of human life. New York: Springer-Verlag. p. 32. ISBN 0-387-90249-X. OCLC 3414838.

The so-called basic law of biogenetics is wrong. No buts or ifs can mitigate this fact. It is not even a tiny bit correct or correct in a different form, making it valid in a certain percentage. It is totally wrong.

- ^ Payne, D.G.; Wenger, M.J. (1998). Cognitive Psychology. Instructor's resource manual and test bank. Houghton Mifflin. p. 352. ISBN 978-0-395-68573-0.

Faulty logic and problematic proposals relating the development of an individual to the development of the species turn up even today. The hypothesis that ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny has been applied and extended in a number of areas, including cognition and mental activities.

- ^ Mayr 1994

- ^ (Danesi 1993, p. 65)

- ^ Desmond 1989, pp. 52–53, 86–88, 337–340

- ^ RICHARDSON, MICHAEL K.; KEUCK, GERHARD (2002). "Haeckel's ABC of evolution and development". Biological Reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society. 77 (4). Wiley: 495–528. doi:10.1017/s1464793102005948. ISSN 1464-7931. PMID 12475051. S2CID 23494485.

- ^ Richards, Robert J. (2008). The tragic sense of life : Ernst Haeckel and the struggle over evolutionary thought. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 136–142. ISBN 978-0-226-71219-2. OCLC 309071386.

- ^ a b Scott F Gilbert (2006). "Ernst Haeckel and the Biogenetic Law". Developmental Biology, 8th edition. Sinauer Associates. Retrieved 2008-05-03.

Eventually, the Biogenetic Law had become scientifically untenable.

- ^ Gerhard Medicus (1992). "The Inapplicability of the Biogenetic Rule to Behavioral Development" (PDF). Human Development. 35 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1159/000277108. ISSN 0018-716X. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-02-09. Retrieved 2008-04-30.

The present interdisciplinary article offers cogent reasons why the biogenetic rule has no relevance for behavioral ontogeny. ... In contrast to anatomical ontogeny, in the case of behavioral ontogeny there are no empirical indications of 'behavioral interphenes, that developed phylogenetically from (primordial) behavioral metaphenes. ... These facts lead to the conclusion that attempts to establish a psychological theory on the basis of the biogenetic rule will not be fruitful.

- ^ "Making visible embryos: Forgery charges". University of Cambridge. Retrieved 27 October 2016.

Rütimeyer's ex-colleague, Wilhelm His, who had developed a rival, physiological embryology, which looked, not to the evolutionary past, but to bending and folding forces in the present. He now repeated and amplified the charges, and lay enemies used them to discredit the most prominent Darwinist. But Haeckel argued that his figures were schematics, not intended to be exact. They stayed in his books and were widely copied, but still attract controversy today.

- ^ "Wilhelm His, Sr". Embryo Project Encyclopedia. 2007. Retrieved 27 October 2016.

In 1874 His published his Über die Bildung des Lachsembryos, an interpretation of vertebrate embryonic development. After this publication His arrived at another interpretation of the development of embryos: the concrescence theory, which claimed that at the beginning of development only the simple form of the head lies in the embryonic disk and that the axial portions of the body emerge only later.

- ^ Gould 1977, pp. 189–193: "Haeckel sensed correctly that His was a far more serious competitor than his empirical critics... His would have substituted a drastically different approach and relegated the biogenetic law to irrelevancy—a fate far worse and far more irrevocable than any odor of inaccuracy."

- ^ Ray, R. S.; Dymecki, S. M. (December 2009). "Rautenlippe Redux -- toward a unified view of the precerebellar rhombic lip". Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 21 (6): 741–7. doi:10.1016/j.ceb.2009.10.003. PMC 3729404. PMID 19883998.

- ^ Barnes, M. Elizabeth. "The Origin of Species: "Chapter Thirteen: Mutual Affinities of Organic Beings: Morphology: Embryology: Rudimentary Organs" (1859), by Charles R. Darwin". The Embryo Project Encyclopedia. Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- ^ Hall, B. K. (2003). "Evo-Devo: evolutionary developmental mechanisms". International Journal of Developmental Biology. 47 (7–8): 491–495. PMID 14756324.

- ^ Lovtrup, S (1978). "On von Baerian and Haeckelian Recapitulation". Systematic Zoology. 27 (3): 348–352. doi:10.2307/2412887. JSTOR 2412887.

- ^ Drost, Hajk-Georg; Janitza, Philipp; Grosse, Ivo; Quint, Marcel (2017). "Cross-kingdom comparison of the developmental hourglass". Current Opinion in Genetics & Development. 45: 69–75. doi:10.1016/j.gde.2017.03.003. PMID 28347942.

- ^ Kalinka, A. T.; Tomancak, P. (2012). "The evolution of early animal embryos: Conservation or divergence?". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 27 (7): 385–393. Bibcode:2012TEcoE..27..385K. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2012.03.007. PMID 22520868.

- ^ Early Evolution and Development: Ernst Haeckel, Evolution 101, University of California Museum of Paleontology, archived from the original on 2012-12-22, retrieved 2013-02-20

- ^ Egan, Kieran (1997). The Educated Mind: How Cognitive Tools Shape Our Understanding. University of Chicago Press. p. 27. ISBN 0-226-19036-6.

- ^ Herbert Spencer (1861). Education. p. 5.

- ^ Hall, G. Stanley (1904). Adolescence: Its Psychology and Its Relations to Physiology, Anthropology, Sociology, Sex, Crime, Religion and Education. New York: D. Appleton and Company.

- ^ Lesko, Nancy (1996). "Past, Present, and Future Conceptions of Adolescence". Educational Theory. 46 (4): 453–472. doi:10.1111/j.1741-5446.1996.00453.x.

- ^ Gould 1977, pp. 144

- ^ a b Gould 1977, pp. 156–158

- ^ Foster, Mary LeCron (1994). "Symbolism: the foundation of culture". In Tim Ingold (ed.). Companion Encyclopedia of Anthropology. pp. pp. 386-387.

While ontogeny does not generally recapitulate phylogeny in any direct sense (Gould 1977), both biological evolution and the stages in the child's cognitive development follow much the same progression of evolutionary stages as that suggested in the archaeological record (Borchert and Zihlman 1990, Bates 1979, Wynn 1979) ... Thus, one child, having been shown the moon, applied the word 'moon' to a variety of objects with similar shapes as well as to the moon itself (Bowerman 1980). This spatial globality of reference is consistent with the archaeological appearance of graphic abstraction before graphic realism.

- ^ a b Taruskin, Richard (2005). The Oxford History of Western Music. Vol. 4. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 358–361. ISBN 978-0-195-38630-1.

Sources

[edit]- Danesi, Marcel (1993). Vico, metaphor, and the origin of language. Indiana University Press. p. 65. ISBN 0253113709.

- Gould, Stephen Jay (1977). Ontogeny and Phylogeny. Cambridge Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-63941-3.

- Desmond, Adrian J. (1989). The politics of evolution: morphology, medicine, and reform in radical London. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-14374-0.

- Mayr, Ernst (1994). "Recapitulation Reinterpreted: The Somatic Program". The Quarterly Review of Biology. 69 (2): 223–232. doi:10.1086/418541. JSTOR 3037718. S2CID 84670449.

Further reading

[edit]- Division of Biology and Medicine, Brown University. "Evolution and Development I: Size and shape".

- Haeckel, Ernst (1899). "Riddle of the Universe at the Close of the Nineteenth Century".

- Richardson, M. K; Hanken, James; Gooneratne, Mayoni L; Pieau, Claude; Raynaud, Albert; Selwood, Lynne; Wright, Glenda M (1997). "There is no highly conserved embryonic stage in the vertebrates: Implications for current theories of evolution and development". Anatomy and Embryology. 196 (2): 91–106. doi:10.1007/s004290050082. PMID 9278154. S2CID 2015664.

- Borchert. Catherine M. and Zihlman, Adrienne L. (1990) The ontogeny and phylogeny of symbolizing, in Foster and Botscharow (eds) The Life of Symbols

- Bates, E., with L. Benigni, I. Bretherton, L. Camaioni, & V. Volterra. (1979). The emergence of symbols: Cognition and communication in infancy. New York: Academic Press

- Gerhard Medicus (2017, chapter 8). Being Human – Bridging the Gap between the Sciences of Body and Mind, Berlin VWB

- Wynn, Thomas (1979). "The Intelligence of Later Acheulean Hominids". Man. 14 (3): 371–91. doi:10.2307/2801865. JSTOR 2801865.